On February 6th, I witnessed two performances back to back with only a 20-minute bus ride in between. Both Huff and Hobiyee were intense, with some beautiful moments, audience participation, and ceremony. Yet it was the combination of both recognizable similarities and stark contrast that struck me the hardest after having witnessed the two performances.

Huff, written and performed by Cree actor Cliff Cardinal and directed by Karin Randoja, was honestly incredibly hard to watch. The story of three brothers struggling to live on a reservation included insights into the prevalent issues of substance abuse, incest and sexual abuse, mental abuse used as punishment in the reserve school system, inadequate parenting, foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, domestic violence, depression (in both adults and children), and suicide. In Medicine Shows, Yvette Nolan discusses this act of exposing poison (pages 7-19), and it is obvious that Cliff Cardinal is intentionally exposing these poisons to the wider public through his nationwide tour of Huff. The discomfort that the performance provoked testifies to this; there were more than a few moments when I felt my pulse racing, my face flushing, and my head become dizzy as visceral reactions to the trauma that was being revealed onstage. Nevertheless, Huff can also be seen as an enormous act of medicine (which Nolan discusses throughout her book). The humour felt in some moments of comic relief showed us that we were still able to laugh, and toward the end of the play Kokhum (the grandmother) conducts a healing ceremony for Wind (the middle brother) after his younger brother Huff’s suicide. Overall, the play can be seen as an grand act of good medicine. Cliff Cardinal, an Indigenous actor who is familiar with the traumas of everyday life for children on reserves, raises awareness of this in front of a mostly-elite audience. (Tickets cost $23; therefore, only those who could afford it attended the show.) In addition, the events that Cardinal depicts can reach deep inside witnesses for whom these traumas trigger certain memories, perhaps making them reconsider something they’ve forgotten or bringing to light repressed thoughts in need of healing. Throughout the performance, it became clear that Huff serves to bring together individuals and communities in order to find support in one another.

Upon exiting the Firehall Arts Centre on East Cordova Street in the Downtown East Side, I seemed to suddenly be aware of my surroundings. Exiting an environment full of awareness-raising and calls for healing into an area in which all of the poisons previously exposed are still very prevalent was absurd. I could not help but feel an enormous discomfort whilst walking to the bus stop and riding the bus for 20 minutes on my way to the PNE for Hobiyee—the Nisga’a New Year celebration.

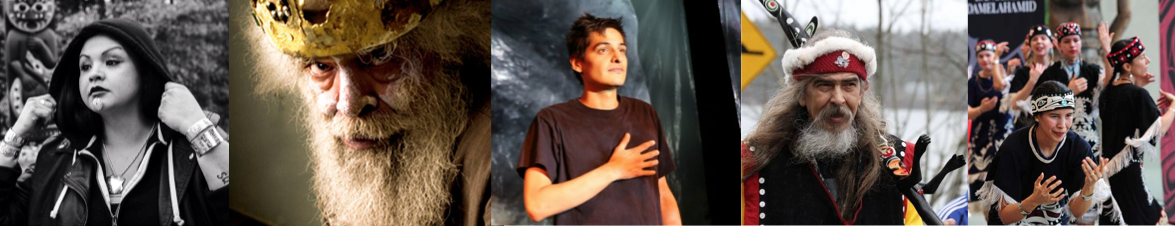

When I arrived at the PNE, I was still feeling some leftover visceral reactions from Huff. Yet upon entering the great hall and finding myself in a crowd of thousands of people—all revelling and celebrating the largest annual gathering of Northwest Coast First Nations dance groups—my spirits were lifted. I remember feeling absolutely in awe whilst witnessing a group of hundreds of drummers (amongst whom was Professor Dangeli) perform a set of songs with synchronised movements to what truly felt like the heartbeat of the Earth. Soon afterward a friend of mine arrived, so we found some seats in the bleachers and watched a number of dance groups perform. My favourite performance (both because of my connection to Professor Dangeli and because of the inventiveness and elegance of their choreographies) was her group, the Git Hayetsk Dancers. I especially enjoyed their innovative “Photographer Dance”, which I suppose was inspired by Professor Dangeli’s PhD research. I was also very impressed as to how quickly the dancers, especially Professor Dangeli, changed regalia in between each dance. Revelry surrounded us, as seen by the food, the packages of fresh fruits handed out to guests, and the smiles on people’s faces. Between many of the songs, a leader with the microphone would sing a joyous “Hooobiyeeeeeee”, which was then echoed by all of the witnesses in the stadium. What a change to the tears, shivers, and headaches that we had experienced earlier at Huff.

Huff and Hobiyee can, on one hand, be seen as performances on opposite sides of a spectrum: one exposing the extreme difficulties of everyday life for Indigenous residents of reserves, and the other celebrating an occasion that has taken place annually for thousands of years (the enormous number of attendees more than testifying to, but rather shouting: “We are still here!”). On the other hand, both performances are acts of medicine. Huff brings together those in need of healing, and Hobiyee can provide that healing through community, tradition, and celebration. Witnessed one after the other, these two performances together told an incredible story of struggle, healing, and resurgence.