On Feb 25, 2016 I attended The Embargo Project At the Talking Stick Festival: Reel Reservations Event at the VIFF.

Before going any further, I highly recommend viewing the trailer here.

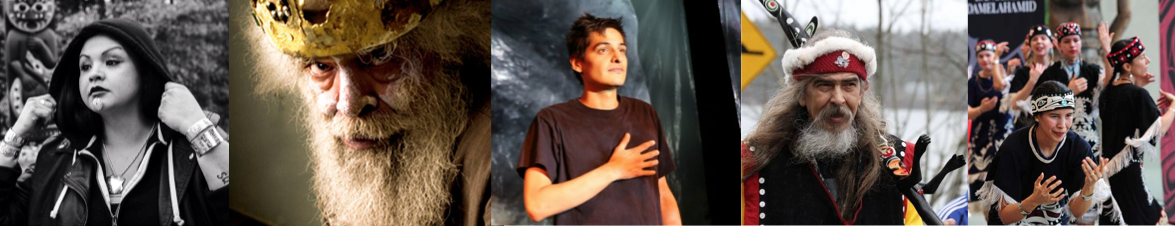

The Embargo project is a collection of short films by Indigenous Women Filmmakers. In this post I will focus on Alethea Arnaquq-Bari’s film, Aviliaq (Entwined). But for a detailed description of the project, bios of the filmmakers, and descriptions of their films go here.

Around the same time as seeing this film, I read the article, “Decolonizing the Queer Native Body,” by Queer Indigenous Feminist,Chris Finley. I have found it really helpful to engage with in my analysis of the film.

Colonization relies on gender violence and control of sexuality in its assertion of control over the settler state. While the role of gender violence in colonization has become a focus point in First Nations and Indigenous studies and communities, sexuality has not. Finley calls for “more open, sex-positive, and queer-friendly discussions of sexuality in both Native communities and Native Studies” (p. 32). She pursues this by 1) examining queered colonial discourses, which define Aboriginal people; 2) critiquing the state’s role in portraying Indigenous people as non-heteronormative because they do not conform to heteropatriarchy; and 3) critiquing Indigenous nation building that uses the settler-state as a model (p. 32).

Heteropatriarchy is perpetuated through media and film, especially through Hollywood films. The mainstream film industry is dominated by male directors and producers. However, the Indigenous film industry in Canada is made up of approximately 50% women (L. Jackson, personal communication, February 25, 2016). It should come as no surprise, then, that these Indigenous women filmmakers are creating space for the decolonization of the queer native body.

Alethea Arnaquq-Baril’s Aviliaq: Entwined is a short romance film set in the arctic during the 1950s. In the film two Inuit women, Ulluriaq and Viivi, try to stay together as lovers even after Viivi gets married. The two women convince Pitsiulaaq, Viivi’s husband to take Ulluriaq as a second wife so they may stay together as lovers, arguing that before colonization Inuit could have polygamous relationships. Pitsiulaaq agrees so that the women may remain together but he asserts that they must keep it a secret so they will not be arrested. Meanwhile, Ulluriaq’s family has decided to leave their territories and move to town. They arrange a marriage between her and Johnny, an Inuk man who lives in town and has a job. When Johnny sees Ulluriaq with Viivi and Pitsiulaaq he calls the police. In the end of the film, Johnny and the police carry Ulluriaq to town in a boat and Pitsiulaaq is arrested. They are all forced apart (Arnaquq-Baril, 2014).

Finley argues that heteropatriarchy is required by colonialism in order for it to “naturalize hierarchies and unequal gender relations” (Finley, 2011. p. 34). In the film we see that heteropatriarchy has been normalized for Johnny and Ulluriaq’s family, so much so that Johnny involves the police in disrupting the polygamous relationship. Ulluriaq, Viivi and Pitsiulaaq also are aware that their relationship is not “normal,” because they try to keep it a secret.

Rayna Green’s concept of the “Pocahontas Perplex,” is the image of Indigenous women represented by colonial discourses as sexually available for white men’s pleasure. Finley argues that the children of Indigenous women and white men become the white inheritors of the land because through white supremacy and patriarchy, inheritance is passed through the father. Therefore, Indigeneity is erased and since colonizing logic requires Indigenous people to disappear for the settler state to inherit the land, when the Indigenous mother gives birth, her Indigeneity must disappear to allow her offspring to inherit the land. In order for this story to work, the Indigenous woman must be heterosexual. Her body and the land must become owned and managed by the settler state (p. 35-36). Ulluriaq’s and Viivi’s love for one another is forbidden because it disrupts the Colonial narrative which allows for the conquest of Indigenous land.

Ulluriaq’s love for Viivi is tied to her love of the land. Her refusal to leave is tied to her refusal to be disconnected from the land. Moreover, staying on the land with Viivi and Pitsiulaaq allows for her to have more control over her own life, whereas life in town is subject to more control by the colonial state. Finley draws on the work of Taiaiake Alfred in her assertion that decolonization relies on sovereignty and connection to land. Finley writes:

“Native people and Native studies need to understand how discourses of colonial power operate within our communities and within our selves through sexuality, so that we may work toward alternative forms of native nationhood and sovereignty that do not rely on heteronormativity for membership.” (Finley, 2011, p. 39-40)

Aviliaq: Entwined, directed by Inuk filmmaker, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril has played a decolonizing role through the uncovering of the control asserted over Indigenous people through heteropatriarchy and control of Indigenous sexualities. Moreover, it demonstrates the ties between sexuality and sovereignty and connection to land. Finley asserts:

“Sexuality discourses have to be considered as methods of colonization that require deconstruction to further decolonize Native studies and Native communities. Part of the decolonizing project is recovering the relationship to a land base and reimagining the queer Native body.” (p. 41)

Alethea Arnaquq-Baril’s work and the work of other Indigenous women filmmakers and artists have a role to play within the decolonizing work of First nations and Indigenous studies, and within the Indigenous communities.

You can find Rebecca’s post on Skyworld, by Zoe Hopkins here

And find Melissa’s review of Bihttoš by Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers here.

Check out the Reel Reservations Embargo Project Prezi here.

References

Finley, C. (2011). Decolonizing the Queer Native Body (and Recovering the Native Bull-Dyke). In Driskill, Q. (Ed.). Queer indigenous studies: Critical interventions in theory, politics, and literature (pp. 32-42). Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Alethea Arnaquq-Baril (Producer & Director). (2014). Aviliaq: Entwined [Motion picture]. (Available from ImagineNATIVE Film, 349-401 Richmond Street W, Toronto, ON, M5V 3A8)