THE DANCE PERFORMANCES

Seeing the two dance works The NDN Way and Greed featured at the Talking Stick Festival’s In Motion definitely stirred up the inner dancer in me. Taking place on February 26, 2016 at the Roundhouse Community Arts & Recreation Centre, I became really immersed in making interpretations on how the choreography was speaking to the dancers’ actions and apparent narratives on Indigeneity taking place.

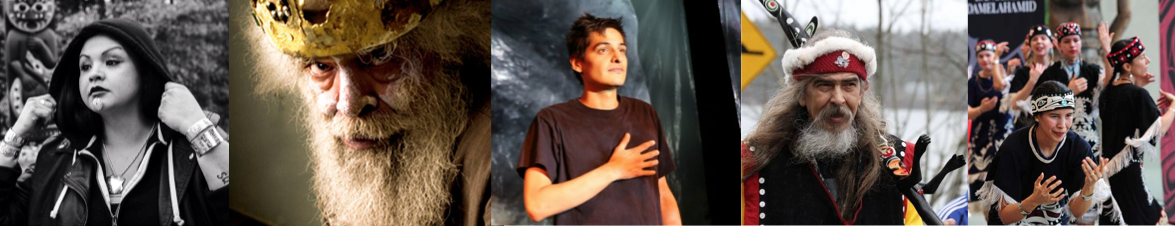

The NDN Way was a duet choreographed by Brian Solomon and performed with Marianna Medellin-Minke. Brian, of Anishnaabe and Irish descent born in a remote Northern Ontario village (Shebanoning/Killarney), is also a Visual Artist and Actor who trained in classical and contemporary dance at the School of Toronto Dance Theatre with an MA in Performance from the Laban Centre in London, UK. He is very interested in engaging with unusual spaces in communities, and is passionate about helping people relearn about their ‘forgotten bodies’ and finding ways of “taking back the space those bodies occupy”. Marianna, born in Torreón, Coahuila, Mexico Mariana Gamar del Carmen, began with studying classical ballet before furthering her studies also at the School of Toronto Dance Theatre. She seeks to create works that are social commentaries which continually deviate within a negative and positive perspective. The NDN Way featured the voiceover of Brian reciting spiritual teachings from Cindy Bisaillon’s 1974 interview with Ron Evans, known as a Métis storyteller who grew up living in the traditional ways in one of the last nomadic Métis communities, along with a mash-up of music from all styles, and seemed to combine moments of playfulness, struggle, and ceremony.

Greed, on the other hand, had a much more dreary and sombre atmosphere which felt more challenging for me to decipher the particular narrative going on, as it drew upon issues surrounding the stock market and the influences of corporate interests and capitalism on Indigenous peoples and cultural practices. Choreographed by Byron Chief-Moon, a member of the Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy in southern Alberta who is an actor, choreographer, dancer, and playwright who seeks to explore dance as a way to incorporate nuances of storytelling through his blood memory. Alongside Byron, three other dancers performed, including Jerry Longboat (Mohawk-Cayuga, Turtle clan, from Six Nations of the Grand River in Southern Ontario who is a visual artist, graphic designer, actor, storyteller, dancer, and choreographer whose performance work is rooted in his personal history and experience and embodies a vision of understanding and honouring the diversity of indigenous culture), Olivia Davies (an independent dance artist and choreographer who honours her mixed Welsh-Metis-Anishnawbe heritage in her contemporary Aboriginal dance-theatre practice through an investigation of the body’s dynamic ability to transmit narrative through exploring shared history, personal legacy, and blood memory), and Luglio Romero (a dancer who has a classical ballet background and has trained at Costa Rica’s Compania Nacional de Danza and SFU’s School of Contemporary Dance). Greed was initially created for the 10x10x10 Dance and Music event held at the Scotiabank Dance Centre in Vancouver during October 2011, where composers were partnered up with choreographers to create a 10 minute dance piece that integrated the composers’ music. Byron Chief-Moon was partnered with composer Jeffrey Ryan, who focused on Ryan’s work Triple Witching, a music piece that refers to “times in the stock market when millions can be won or lost”. The original 10 minute piece served as a starting point that became this version we saw, in which Chief-Moon aspired to expand the choreographic language to interweave First Nation’s concepts of greed and imbalance, and as a way to “highlight Canada’s systematic disenfranchisement of First Peoples from the land and its resources”.

REVIEW HIGHLIGHTS (from past performances of Greed):

“The challenge for the choreographer comes with being confronted with something outside of their normal range of choices—and that should provoke completely new ideas. That’s proven true for local choreographer Byron Chief-Moon.”

-Janet Smith, Georgia Straight, Oct 2011

“Longboat’s interpretation explores greed and remorse among First Nations people, addressing the imbalance created by early contact with Europeans and the subsequent loss of lands and culture. His choreography is a blend of native and contemporary dance. While sincere in performance, the dance movement itself needs more definition.”

-Paula Citron, The Globe & Mail, June 2015

WITNESSING

Throughout the whole performance, I was writing down notes about the kinds of movements and expressions taking place as I interpreted them, attempting to reflect on found meanings that may have been rising out of movements and choreography (as I am a dancer myself). After reflecting on these notes as a whole, I found that Ric Knowles’ discussion on rape and sexual violence on First Nations women in his article “The Heart of Its Women” can also be related to aspects of choreography and context found in these performances. Knowles introduces the idea of ‘re-membering’ as a way of working together “to resist the global scope of the colonial project… to serve as agents of anticolonial and anti-imperial resistance and healing” through embodiment (137). In relation, he brings awareness to the idea of individual and community ‘dismemberment’, which he describes as “agents of ethnic cleansing and cultural genocide”, and states that it “can be healed only through an embodied cultural re-membering” (136-7). Since Solomon and Chief-Moon have also stated that their practices seek to explore cultural reconnection, I found particular aspects of their choreographies in which I feel Knowles’ notion of ‘re-membering’ through embodiment has come out.

The NDN Way

example 1

The choreography started off slowly with both Brian and Marianna lying on the ground, curled up in a fetal position facing away from the audience. Marianna began by making subtle gestures, turning into slow pulses, and then eventually getting up onto her hands and knees, crawling in an animal position as the voiceover stated “animal brothers and sisters share life”. There were other moments throughout their performance when these animal-like movements would be made too, and I saw these motions in combination with having heard this line from the voiceover as a ‘re-membering’ of our connected relation with the animals, and as a way of showing how this connection is rooted in our bodies through mimicking their actions.

example 2

In another scene later on, the voiceover states “we see in the nature around us our inner reality”. In response to this, the dancers, who had been holding eye contact with each other while kneeling down at opposite ends of a long box for awhile, look away to stare directly at the audience, remaining this way as they began a synchronized movement of bringing the sides of their heads together, and then sliding downstage towards the audience with their arms reaching out to us. Soon after, this connection was broken as they separated and moved back upstage into the position they once were in. Through this literal attachment of their bodies and minds coming together, I saw this as a temporal moment of ‘re-membering’ how we all share the same nature together as a form of ‘anticolonial resistance’. With a kind of cycle occurring through their return and disconnection after, I thought this could have stood as an act of ‘dismemberment’, showing that cultural reconnection is not always easy to hold on to as an effect of the strong forces of Knowles’ term ‘ethnic cleansing’.

example 3

In a scene closer towards the end, Brian goes on a vision quest. Marianna transitions the set on stage, turning the boxes into angular directions that appeared to be models of buildings, while he enacts smoking a pipe with tobacco. The voiceover states “you’ll learn something about yourself” as he closes his eyes and sits on his knees. He starts doing this pulsing motion that resembles a kind of movement in contemporary dance of suspending oneself onto the bridge of their feet, where his lower thighs were lifted up as he balanced his whole body using the strength of his toes. This action was as if he was beginning to build up strength through his body through a ‘re-membering’ of his purpose as an individual through the vision quest. After this moment, he transitioned into a deep lounge position towards us, bringing his arms up and circling them at rapid speed around his body, which illuminated a kind of glowing light in interaction with the spotlight from above. To me, this signified a complete breakthrough of finding strength through a ‘re-membering’ of his own cultural self in relation to this ceremonial practice.

Greed

example 1

Compared to having voiceovers to help describe the visual enactments of the dancers, having no verbal words in Greed may speak to the silencing of Indigenous voices as a result of what Knowles’ discusses as the ‘colonial project’, as dancers appeared to be encapsulated in this corporate dreary world and are seeking ways to escape it through attempts of ‘re-membering’.

example 2

At the beginning, the tone of the dance was established as what one of my dance teachers has described as a ‘collective consciousness’, in which the group of dancers existed in the same time and space by being with each other, with the three men lifting up Olivia into the air as she reached her arms above into a ‘V-shape’ position. I thought that this demonstrated the community aspect Knowles brought up in relation to embodied cultural ‘re-membering’, immediately asserting that each of the dancers are in this journey of undertaking struggle together. Much of the choreography that followed featured much more violent imagery of suffering and pain, of which included slow, dragging, zombie-like steps and twisted and distorted ‘ronde-de-jambe’ ballet movements (circling of the legs with feet touching ground) by Olivia, sudden collapses onto the ground, intense trembling and shaking, sharp angular distortions of the arm hitting parts of the body, and a gesture of always covering one side of the face with their hands.

example 3

I found that the choreography in this performance combined more traditional movements of Indigenous dance forms with contemporary and classical dance styles compared to The NDN Way. In one scene, one of the male dancers started doing these motions that seemed to combine split jumps and deep lounges/knee bends (as in jazz dance) with hops and steps from traditional ways of moving in Indigenous cultures. This followed by stepping turns that slightly resembled turns in contemporary dance called ‘shinay’ turns, and also appeared to be acting as bird-like hops with the opening of his arms, which immediately connected me to an image of a thunderbird or eagle. In Knowles’ article, he included a quotation from Sandra Richards, in which she states that “cultural memories and traditions passed on in unspoken, embodied, and performative ways through everyday habit and ritual can work to resist attempted erasures” (143-4). I think that the performativity of these embodied actions of a fusion of traditional and contemporary dance forms and imagery can speak to this as a moment of ‘re-membering’.

ending thought

I feel that these dancers in both performances were able to embody a place of ‘re-membering’ they may not have otherwise been able to reach through other kind of ways (such as verbally). Through their activated bodies, they were able to drive an internal force that pushed them to engage in these moments of ‘re-membering’ in light of their shared experiences of pain and struggle, and were able to release that momentum for us as the audience to become embraced by.

—

See more! (presentation slides):

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1KXRFJT8yGJcd84YCkyKMrN_75KAUD6k_oEsadRhY28Y/edit?usp=sharing