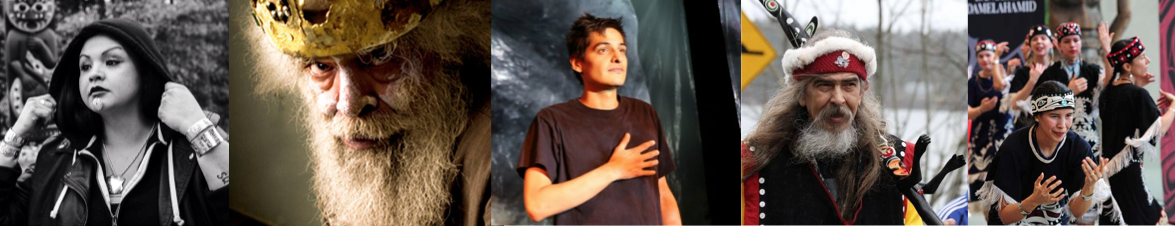

On the 15th of January I had the honour of attending the Lalakenis All Directions Feast, hosted by Beau Dick at the AMS Nest. In addition to my involvement as a witness, I had been asked to involve myself as an organizer, participated in the Pipe Ceremony, and last minute danced a mask (Bakwus).

Beau Dick or Walas Gway’um is a hereditary chief, artist, carver, and teacher of the Kwakwaka’wakw people specifically from Alert Bay. Beau hosted this feast to serve many purposes; as a call to action to all peoples of North, Central, and South America to acknowledge violence perpetrated by the government to Indigenous peoples (and to begin to undo the hurts caused by this violence), as a means of sharing spiritual and physical wealth, to honour and open the way for the Lalakenis All Directions exhibition that was to open the next day at the Belkin Art Gallery, and to provide a spotlight for those in the community doing art and engaging in activism to share with us all.

Because the event lasted an entire day, it would be an absurd undertaking for me to try to describe it all here. The particular events that I will elaborate on in brief here are the sharing of a smallpox song by Lorne, Jeneen Frei-Njootli’s performance piece, and the Pipe Ceremony.

Lorne (from Montana, I do not know his full name or nation), early in the event shared a smallpox song and detailed how it came to him. He described a time in his tribe’s history when smallpox was ravaging the community. He said that one family afflicted with the disease cloistered themselves away in a cave to prevent the smallpox from spreading to others. He said that their voices found him, passed along the song, and asked that he not forget about them.

Tearfully, he shared the song with us. I think it’s safe to say that no one in the room was left with dry eyes. I could help but link this performance to Yvette Nolan’s notions of survivance and remembrance. Lorne strongly acknowledged his love, connection, and gratitude to his ancestors, and in that moment we were all able to share in that gratitude and connection. The tremendous love between they and him filled the room and asserted the intentionality and radical decolonial love underlining Indigenous survival and thriving.

The Pipe Ceremony, which happened earlier in the event, was hosted by Gyaauustees, the pipe keeper and carver, to provide the opportunity for Beau’s grandson, Gavin, to receive a pipe. The ceremony was also an opportunity for many of us who had been through trauma or who had lost loved ones recently to receive support and healing.

I myself had lost my grandmother a few weeks prior to the event and entered into the ceremony with a heavy heart. It was transformative, and deeply moving to have been able to be a part of Gavin’s entrance into his community as a man, in a sense, imbued with new spiritual purpose and responsibility, bestowed upon him by his elder’s deep love for him.

Finally, Jeneen Frei-Njootli performed a unique piece by playing a caribou antler manipulated with her hands and breath, and played percussively. The sounds the antler produced were reminiscent of the landscape that raised her- the Canadian north, traditional territory of her Gwi’chin people. I couldn’t help but think of the significance of the use of the caribou, an animal strongly connected to Gwi’chin spirituality, cultural expression, and material survival, and how perfectly it recreated the experience of its and her homeland.

I feel as though each of these acts was an act of love, forgiveness, an underscoring of Indigenous presence and thriving, and of course, acts of ceremony. Additionally, in Lorne’s song and in the Pipe Ceremony in a more private sense, there were elements of “poison exposed” referring to the release and exposure of negative or traumatic incidents for the purpose of lifted the weight of colonial trauma. This exposed poison was then soothed by the day’s ceremonies and the sharing of openness and love.

I would like to leave you all with the following question regarding this notion of poison exposed: Is there sense in exposing poison simply for the outcome of personal release, or must this exposure be paired with ceremony or structure in order to leave the individual exposing this poison in a better state than they began in?

Showing at Audain Gallery, Vancouver from January 14 – March 12, 2016

Showing at Audain Gallery, Vancouver from January 14 – March 12, 2016