On February 26th I had the amazing honour and privilege of attending the annual “From Talking Stick to Microphone” poetry slam, which was started in 2011 by (one of my heroes) Blackfoot poet Zaccheus Jackson Nyce. He sadly passed away in 2014, and so the event continues in his honour. I will talk more about him in just a bit.

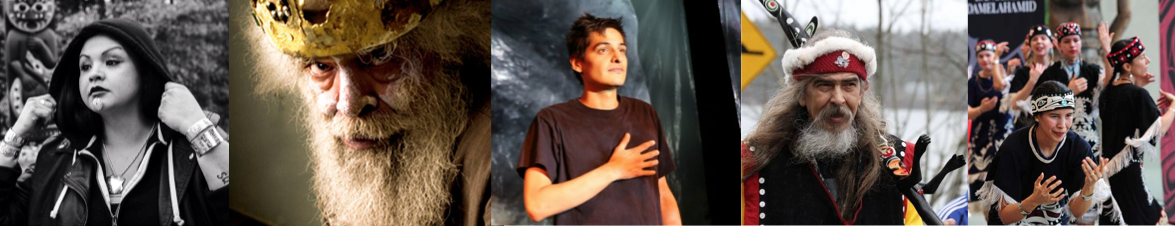

The night featured some of Vancouver’s most talented Slam Poets and musicians.

The night was hosted by the ever incredible and ridiculously hilarious Tahltan/Kaska performing artist Nyla Carpentier, and was DJ’d by Vancouver-based Cree turntablist DJ Kookum.

The event itself consisted of three sections.

The first part featured youth poets from the Urban Native Youth Association, the second part featured the 2016 Van Slam team as well as Van Slam all-stars. The last section was an open slam.

So many of my dearest friends and heroes performed that night and it was absolutely unreal to have so many rad people under the same roof.

Here are a few examples:

My dear, dear friend Molly Billows from Homalco, a brilliant poet, UBC FNIS graduate, and youth facilitator. Her work touches upon reconciling her father’s whiteness with her Indigeneity and radical anti-colonial love. So we have connections to Nolan’s concepts of poison exposed and Necollet there.

My good friend Valeen Jules from Kyuquot (ky-YOO-kit) Sound on the Island: a ferocious writer and activist. She volunteered to be fire-keeper on Burnaby Mountain during the Kinder Morgan protests—where she kept the fire burning for protestors for up to 19 hours a day for 11 days straight. Her poetry is poison exposed in motion. One of her poems, which I don’t know the name of, compares settler-colonialism, as it is experienced in Indigenous communities, with the Hunger Games to shed a light on the extra-judicial violence that the state commits every day on Indigenous bodies. I am so in awe of her work, and she came up to me that night and told me my own writing was “deadly” and I nearly fainted from being so starstruck. She’s incredible.

The incomparable Jillian Christmas from Markham Ontario:

She’s not Indigenous but was nonetheless honoured as a Van Slam favourite not only because of her amazing poetry, but also because of the solidarity work she has done with Indigenous youth and with land-based resistance. One of the poems she read was for the Unist’ot’en Camp in Wet’suwet’en territory, which she wrote for an Unist’ot’en Camp fundraiser that I helped organize back in September. I love her dearly, she’s a beautiful weaver of words and a breathtaking musician, and I’m glad to call her one of my friends.

Zoey Pricelys Roy:

Métis, Cree, and Dene, Youth activist. Spoken word poet and Community leader. She also co-hosted the night. I don’t know too much about her personally, but her performances were incredibly powerful and moving. According to her bio on the event page, she left home at 13 and was incarcerated before the age of 15. It was through Youth Faciliation and various outlets of creativity (one of them being spoken word poetry) that she began her path toward healing. For Zoey too, spoken word represents Nolan’s concept of medicine.

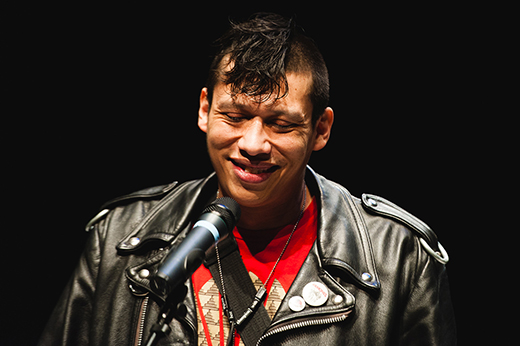

Mitcholos Touchie, Nuu-Chah-Nulth from Tofino.

He’s a dragon poet with words of fire. His work, like everyone I just mentioned, exposes poison, and does so in the most unforgiving fashion. Whether calling the world he grew up in a ‘swirling pile of shit’, or announcing his bid to start a war party against the state in the next local election—his work ferociously exposes the disconnections that colonization has left in his life. His poetry is thus also medicine, as it allows him to reconnect to himself and his commitment to reviving his indigeneity and maintaining his sobriety. He has a frequent refrain where he rejects his status number and maintains “my name is Mitcholos motherfuc*ing Touchie!”. He’s definitely one of my heroes, and he actually pulled me aside during one of the breaks to perform outside for the people waiting in the rain to get in, which was a huge honour. A short clip of this performance, shot my Mitcholos himself, can be seen here:

But I want to talk more about this guy, Zaccheus Jackson.

He started this event in 2011 and sadly passed away in 2014. I did not knew him super well, but my gosh was I a fan. He came in one time as a guest speaker for this youth program I was a part of with Urban Ink, and he told us the story of how spoken word came into his life, and for him, like so many of the poets I’ve discussed, poetry was medicine, and it came by accident.

He was living on the streets of East Van and had a drug addiction. And one Monday evening he walked passed Café du Soleis where the Van Slam happens every night. He didn’t even know what a slam was, but he said he did a lot of writing to keep him grounded. And so he went in and tried it out and people absolutely loved him. He described the feeling of being heard and loved that night as the most ‘potent high he had ever experienced’. And he kept doing it, eventually breaking his drug habit

And so this this event, “From Talking Stick to Microphone”, doesn’t just represent the legacy of a beloved poet, but it represents the legacy of survival. Of futurity. Of resistance. Of connection.

What made him special, as noted by many, was his ability to connect with others. He built a community wherever he went, and with whoever he spoke to or with. People loved him.

“Broad shoulders, huge catlike grin, a large man larger than life. He held space in a room and had a laugh that was memorable, these are just some ways those who’ve known Zaccheus described him.” – Lena Recollet, Urban Native Mag

“Nobody could speak faster than him. His voice would just capture a room. It was a beautiful baritone that just shook the walls.” -Jillian Christmas, thestar.com

To see his magic yourself, check out his booming performance of fan-favourite “In Victa” below:

We miss you Zacc.