Who is Jack Charles?

Jack Charles, “Addict. Homosexual. Cat Burglar. Actor. Aboriginal.” reads the tagline for the movie poster of Bastardy, the documentary about him directed by Amiel Courtin-Wilson.

Charles, 73, a Koori man born in what is colonially known as Australia in 1943, was thrown into the Australian assimilationist project at only 10-months old, when he was taken from his mother and put into the Box Hill Boys’ Home where he was the only Indigenous child. In his play, Jack Charles V The Crown, he describes this period in his life as being a “soldier of the cross”.

Theatre has been without a doubt a significant force in his life, and continues to be. At the age of 28, he was instrumental in establishing Aboriginal theatre in Australia, wherein he produced a show with Indigenous actors living in hostels titled, Jack Charles is Up and Fighting.

Charles later when on to establish a prominent film career, while also becoming an addict to heroin, a burglar, and a convict serving multiple sentences—all while navigating his sexuality and dark past in Box Hill and foster care.

Storytelling as re-humanization and decolonial love: connecting Jack Charles v The Crown with the work of Dana Claxton, Yvette Nolan, and Karyn Recollet.

As a spokenword artist and actor, I am partial to the idea that stories, whether told by us or about us, encompass a large part of our identities. I bring this idea into my studies within FNIS, which has lead me to being particularly interested in oral tradition, storytelling, and performance art, as well as the role each may play as potential decolonial forces.

For my first paper in this class, I argued that Jack Charles’ play was an act of rehumanization in the face of the dehumanizing forces undergirding the Australian colonial project; namely the Australian legal system and its missionary school history, which both sought to contain Charles throughout his life. For this presentation, I will start by touching upon a few points I make in this paper without giving away too much detail, and I will also draw from some of the literature in this class to support this claim that Charles demonstrates decolonial praxis through his theatre work.

Through my studies in FNIS, it has been made clear that storytelling and oral tradition carry a lot of potential as decolonial forces. This idea that I mentioned, for example, that storytelling comprises our identities is echoed by Cherokee author Thomas King, who is credited for authoring the popular line that stories are “all that we are”. He employs this adage to interrogate the role storytelling has played in the colonialism of Indigenous peoples–namely how ideologies of difference that construct Indigenous peoples as less than human are deployed (even to this day) to justify land dispossession. Thus, Thomas King is arguing that reclaiming the ability to tell one’s story is a decolonial force. Quite literally, For King, to tell one’s own story, under colonialism, is an act of re-humanization.

This idea of re-humanization is central to an artist we have studied already in this class, Lakota artist Dana Claxton, who’s exhibit “Made to be Ready” at the Audain gallery was presented on two weeks ago, which pays attention to Indigenous womanhood and sovereignty in primarily the Plains First Nations. I was really struck by this presentation, so that day I did some research on Dana. As she was promoting “Made to be Ready”, she came out with “6 ways to resist Art’s dehumanization of Indigenous peoples” which was published into a blog post by the same name, by the Canadian Arts Foundation. Much like how Thomas King gives focus to the role of storytelling within de/colonization, Claxton does the same with art and museum culture.

I had Claxton’s six reflections in mind as I watched Jack Charles V The Crown, and for my paper this month I attempt to trace links between the 6 reflections for rehumanization with Jack Charles’ play.

I won’t dive into the parallels here because I did so for my paper. But one argument I elaborate in the assignment is that Jack Charles’ pottery humanizes him, in the face of ongoing colonialism, by connecting him with the earth the clay comes from, and his ancestors who may have also done pottery.

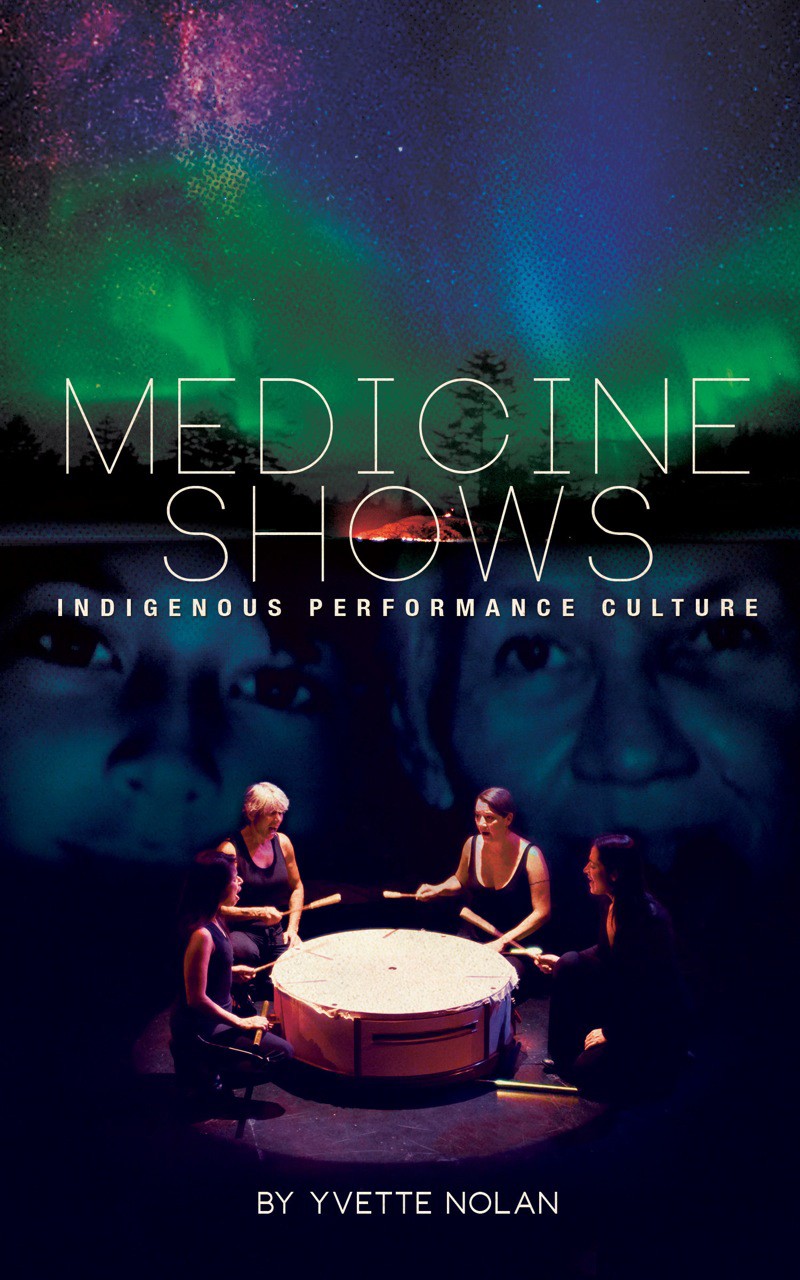

I was particularly struck by Charles’ pottery as a form of storytelling, and thus rehumanizing force, and after reading Yvette Nolan’s 2015 book Medicine Shows , I was able to articulate how.

Medicine→ which is about reconnecting and being cognizant of the ‘interconnectedness of all things’ (1). I believe Charles did this with his poetry, and his story about how the clay comes from the sediment which travels from mountains–and thus pottery connects one to the land and to their ancestors.

Remembrance→ “Indigenous theatre artists make medicine by reconnecting through ceremony, through the act of remembering” (3)

Ceremony and audience→ “Creating ceremony onstage is powerful medicine. Like all medicine, ceremony is about reconnecting: reconnecting the artist to […] ancestors, the viewer to lost histories, the actor to the audience” (55)

It can be argued that, when seen through the lens of Nolan, that Jack Charles demonstrates rehumanization through creating medicine, through reconnecting with his ancestors and with himself, by centering his voice.

I want to end by saying that Charles demonstration of re-claiming his voice, story, and history, in the way it challenges the dehumanizing forces of colonialism, also demonstrates Cree hip hop scholar Karyn Recollet’s notion of “Radical Decolonial Love”, explored in her chapter “For Sisters” from Drew Hayden Taylor’s seminal collection of essays Me Artsy.

She explains, “Radical decolonial love requires a shift in focus away from the heteronormative, settler colonial practices of ownership and control over Indigenous lands and bodies, into a space that produces the vocabulary and language to speak of its impact on our relationships with other sentient beings” (104). Charles demonstrated a radical decolonial love for himself, through his defense testimony at the end of his play, wherein he implicates Australian settler-colonialism and assimilationist projects for fostering his life of crime, drugs, and trauma. He takes focus away from the silencing process of Australian law, and instead foregrounds his own voice and experience, and sheds light on how his life, body, and relationships were affected by colonialism.

Questions for further discussion:

- What are other ways that Jack Charles’s play may have reverberated anti-colonial praxis?

- Were there advantages to Charles’ use of a live band in his storytelling? Other than aesthetic, why do you think he included one?